Biographical Sketch

Intellectual Biography

I am a humanistic scientist. In 1965 I was awarded the B.A. in Geology (geomorphology) from Indiana University; in 1973 the M.A. in Anthropology (biological) from Cornell University; and in 1981 the Ph.D. in Anthropology (biological) from Cornell University. I began my graduate studies in anthropology at Indiana University, then moved to Cornell which was closer to my interests. My intellectual gurus were David Bidney and Georg K. Neumann at Indiana, and Kenneth A.R. Kennedy and John V. Murra at Cornell.

In various capacities I have served as a visiting instructor of anthropology at Indiana University; University of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada); Mount Royal College (Calgary, Alberta, Canada); Cornell University (Ithaca, NY); University of Massachusetts (Amherst); Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Investigations (Caracas); and the Biology Section of Prince of Songkhla University (Pattani, Thailand). (The last two were invited Fulbright Fellowships).

Turning to influences in the development of my career, especially those related to spiritual ecology, like everyone, my parents influenced me initially. My Father was an avid hunter and fisherman. My Mother loved trees, flowers, and the changes of the seasons in our home in suburban Indianapolis. On holidays we often visited lakes in wooded areas, sometimes camping. Yellowwood Lake in Brown County in southern Indiana was a favorite weekend retreat. During summer holidays we visited lakes in Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. My parents and these experiences instilled in me a love of nature. My grandfathers were conservationists, although I did not learn that until much later. There may have been some influence from them through my parents (Sponsel 2018).

During the senior year of my undergraduate studies, I had to take some social science requirements, and anthropology seemed most interesting by far. After courses in physical anthropology and cultural anthropology I was hooked on the subject. However, since I had already completed many courses in geology and also one in physics and another in chemistry, I decided to first finish the geology degree. I accumulated the equivalent of a second major in geography as well. While pursuing graduate studies in anthropology at Indiana University, I took a course on ornithology that was most interesting and enjoyable, especially the early morning field trips on Saturdays. During graduate studies at Cornell, I completed a course in biological ecology and another in vertebrate ethology. These experiences formalized my interest in nature in a scientific and academic sense.

For my doctoral dissertation on the behavioral ecology of Yanomami predation in the Venezuelan Amazon, I was most fortunate in affiliating with the Department of Anthropology at the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Investigations (IVIC) in Caracas (Sponsel 1981). My approach to behavioral ecology simply researched the interrelationships between behavior (including culture) and ecology (including ecosystems and human predator-animal prey interactions). Eventually I was asked to teach a graduate seminar course on cultural ecology. This was the beginning in what would become the explicit and systematic study of ecological anthropology and its applied dimension called environmental anthropology.

In 1981, I was hired to develop and direct the Ecological Anthropology Program at the University of Hawai`i. However, by 2000, after many years of teaching ecological and environmental anthropology, I concluded that secular approaches alone, although absolutely indispensable, were clearly insufficient. Far more was needed. I turned to religion because of its power in motivating and guiding adherents and its various resources (Gardner 2006). I identified the new field of spiritual ecology. I was convinced that spiritual ecology might finally help turn things around for the better.

Spiritual ecology may be defined as the vast, diverse, complex, and dynamic arena of interactions of religions and spiritualities with ecologies, environments, and environmentalisms, all plural to recognize their substantial variety (Sponsel 2014a). Others prefer labels like religion and ecology, religion and nature, or religious environmentalism.

Although some colleagues at the University of Hawai`i were disturbed by my interest in spiritual ecology, one even sabotaging the doctoral dissertation defense of one of my students who pursued the subject, through my commitment, persistence, and scholarship I transcended such resistance and obstruction to flourish in my research and publications. However, the word spirituality still bothers some people in my department and many far beyond.

Spirituality is increasingly becoming a legitimate subject for serious scientific and scholarly research (e.g., Chang and Boyd 2011). Spirituality is important because many people identify themselves as spiritual but not religious, while most who are religious are also spiritual. Thus, ignoring spirituality ignores a vast portion of human interests and experiences. Moreover, spiritual experiences in nature are the underlying motivation for much of environmentalism and conservation (e.g., Berry 2015, Stoll 2015). Wilderness prophet John Muir is a prime example (Worster 2008).

A major influence on the development of my interest in spiritual ecology remains Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim who organized a series of conferences on different world religions and ecology at Harvard University in the late 1990s. I found time and funds to attend three of them, those on Buddhism, Indigenous Traditions, and the concluding conference. I published a chapter in each of the books from two of the conferences (Sponsel 1997, 2001). Since 1998, I have been on the Advisory Board of the Forum on Religion and Ecology (FORE) which was first based at Harvard University and is now at Yale University. I provide information for the FORE website, such as my course syllabi and bibliographies, as well as items of interest for the eNewsletter. (See https://fore.yale.edu/).

Another major influence is Bron Taylor in Religion at the University of Florida. He established the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture (ISSRNC) in 2007. I was a founding member. I attended its inaugural conference in Gainesville, and my paper was subsequently revised and published in the society’s Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture (Sponsel 2007). Also, Taylor (2005), as Editor-in-Chief of the Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, thoughtfully designated me among several others as an Associate Editor for the assistance that I provided.

These inspiring engagements with Tucker, Grim, and Taylor greatly strengthened my commitment to spiritual ecology because I found highly respected and encouraging academic colleagues.

In recent years, my scholarship in this relatively new field has been increasingly recognized. In 2012, I published my book Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution with Praeger. On May 17, 2014, it was the winner in the Science Category at the Green Book Festival in San Francisco, CA. (See https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2014/05/28/spiritual-ecology-book-wins-at-green-book-festival/). Also, I have been honored by invitations to publish on this subject in international refereed venues, such as a featured bibliographic essay on 125 books in the college and university acquisition librarian magazine CHOICE (Sponsel 2014a), and in the online Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion (Sponsel 2019).

While pursuing field research with the Yanomami in 1974-75, and thereafter following the literature on them for decades and occasionally publishing an article about them, I never thought about their spiritual ecology. However, when I read the 2013 book The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman co-authored by Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, respectively a Yanomami shaman and a French anthropologist, then I realized that the Yanomami are practical spiritual ecologists. Previously I had missed what is a very vital part of the heart and soul of their culture, society, and daily life. For the Yanomami, their tropical rainforest habitat is simultaneously a biophysical and spiritual environment (Sponsel 2014b, 2022).

Since 1986, in collaboration with my wife, Dr. Poranee Natadecha-Sponsel, I have been visiting Thailand during summers to pursue field research on Buddhist ecology and environmentalism, in more recent years encompassing a focus on sacred caves in particular. The latter explores the possible ecological interrelationships among sacred caves, Buddhist monks, bats, forests, biodiversity, and conservation. A chapter we published in Thailand on these interrelationships was reprinted in the anthology This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment edited by Roger S. Gottlieb (Sponsel and Natadecha-Sponsel 2003, 2004). A world-wide survey of sacred caves was also published (Sponsel 2015). As another example, we were invited to co-author the chapter “Buddhist Environmentalism” for Teaching Buddhism: New Insights on Understanding and Presenting the Traditions co-edited by Todd Lewis and Gary DeAngelis (Sponsel and Natadecha-Sponsel 2017). Sacred caves are a most appropriate research focus for me because it engages and integrates diverse interests from geology, anthropology, and religious studies.

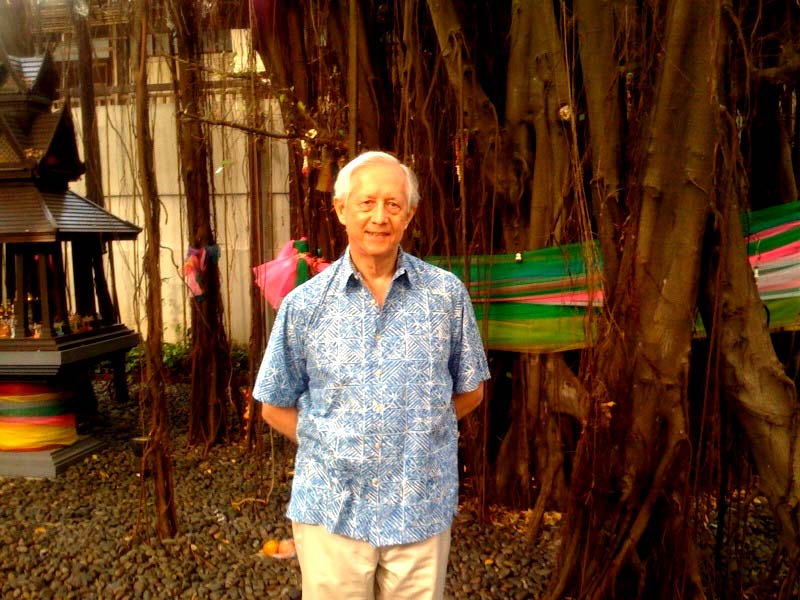

Observing the influence of Buddhism and Animism on Thai interrelationships with nature also influences my interest in spiritual ecology. Clearly, Thai culture is spiritual ecology in practice in many ways and degrees. For instance, various trees, forests, mountains, and caves are considered sacred. Buddhist temples and monks may be associated with some of them as well (e.g., Darlington 2012). Reflecting Animism, there are spirit houses in most yards, including those of homes, businesses, and government facilities (Warren and Broman 2005).

I pursue spiritual ecology not only because it is most interesting, but also because of its actual and potential positive and hopeful contributions to environmentalism and conservation as well as to science and academia. The more I study the subject, the more I realize that spiritual experiences in nature have generated much of the concerns and actions in environmentalism and conservation. Moreover, the existential crisis of global climate change with marked increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events throughout the world may become a catalyst generating accelerating interest in spiritual ecology and its practical relevance and applications.

I am the founder and director of the modest Research Institute for Spiritual Ecology (RISE) http://spiritualecology.info. The website offers extensive information on the subject, including course syllabi and bibliographies. Related to this is my teaching of ANTH/REL 443 Anthropology of Buddhism, ANTH/REL 444 Spiritual Ecology, and ANTH/REL 445 Sacred Places. It also contains an extensive bibliography on Buddhist ecology and environmentalism, the subject of my next book titled Natural Wisdom.

From Fall 2015 through 2019, I served through email as an invited voluntary consultant for the development of the exciting new anthropology graduate program and spiritual ecology in particular at the Royal Thimphu College in Bhutan: http://www.rtc.bt/.

On the above, and a diversity of other subjects, I have published numerous journal articles, book chapters, and entries in more than a dozen encyclopedias, as well as seven edited books.

For more information see:

- https://anthropology.manoa.hawaii.edu/leslie-sponsel/

- https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/2003432447_Leslie_E_Sponsel

References Cited

- Berry, Evan, 2015, Devoted to Nature: The Religious Roots of American Environmentalism, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Chang, Heewon, and Derick Boyd, eds., 2011, Spirituality in Higher Education: Autoethnographies, Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Gardner, Gary, 2006, Inspiring Progress: Religion’s Contributions to Sustainable Development, New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company/Worldwatch Institute.

- Kopenawa, Davi, and Bruce Albert, 2013, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sponsel, Leslie E., 1981, The Hunter and the Hunted in the Amazon: An Integrated Biological and Cultural Approach to the Behavioral Ecology of Human Predation, Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International (Cornell University Doctoral Dissertation).

- _____, 1997 “A Theoretical Analysis of the Potential Contribution of the Monastic Community in Promoting a Green Society in Thailand,” (with Poranee Natadecha-Sponsel) in Buddhism and Ecology: The Interconnection of Dharma and Deeds, Mary Evelyn Tucker and Duncan Williams, eds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions, pp. 45-68.

- _____, 2001, “Is Indigenous Spiritual Ecology a New Fad?: Reflections from the Historical and Spiritual Ecology of Hawai`i,” invited for Indigenous Traditions and Ecology: The Interbeing of Cosmology and Community, John Grim, ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions, pp. 159-174.

- _____, and Poranee Natadecha-Sponsel, 2003, “Illuminating Darkness: The Monk-Cave-Bat-Ecosystem Complex in Thailand,” in Socially Engaged Spirituality: Essays in Honor of Sulak Sivaraksa on His 70th Birthday, David W. Chappell, ed., Bangkok, Thailand: Sathirakoses-Nagapradipa Foundation, pp. 255-269. (Reprinted in This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment, Roger S. Gottlieb, ed., 2004, New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 134-144).

- _____, 2007 “Spiritual Ecology: One Anthropologist’s Reflections,” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 1(3):340-350.

- ______, 2012, Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution, Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers.

- ______, 2014a (April), invited Feature Article – “Spiritual Ecology: Is it the Ultimate Solution for the Environmental Crisis,” CHOICE 51(8):1339-1342, 1344-1348.

- _____, 2014b, “The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman, Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert,” invited for Tipiti: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America 12(2):172-177 (Article 13) http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1193&context=tipiti.

- _____, 2015, “Sacred Caves of the World: Illuminating Darkness,” in The Changing World Religions Map, Stan Brunn, and Donna A. Gilbreath, eds., New York, NY: Springer, 1:503-522.

- _____, and Poranee Natadecha-Sponsel, 2017, “Buddhist Environmentalism,” invited for Teaching Buddhism: New Insights on Understanding and Presenting Traditions, Todd Lewis and Gary Delaney DeAngelis, eds., New York, NY: Oxford University Press, pp. 318-343.

- 2018, “Love in/of Nature: Biophilia, Topophilia, and Solastalgia,” invited for Love in the Time of Ethnography: Essays on Connection as a Focus and Basis of Research, Lucinda Carspecken, ed., Lanham: Lexington, pp. 17-34.

- _____, 2019, “Ecology and Spirituality” invited for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, John Barton, ed., New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- 2020, Religious Environmental Activism in Asia: Case Studies in Spiritual Ecology (published by the journal Religions as invited guest editor). https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/Religious_Environmental_Activism_Asia.

- Sponsel, Leslie E., 2022, “Reconnecting Humans with Nature: Reflections from Spiritual Ecology,” invited for free access eBook Spiritual Ecology: Integrating Nature, Humanities, and Nature, Elis Rejane Santana da Silva and Eraldo Medeiros Costa Neto, eds., Ponta Grossa, Brazil: Atena Editoria, Chapter 2, pp. 17-35. (The book by mostly Latin American authors is in Portuguese, Spanish, and English. My chapter is in English. In the Table of Contents in the attachment here click on the chapter title or scroll to page 17. Also, the publisher’s website has the book: https://www.atenaeditora.com.br/ebooks?titulo=Ecologia+Espiritual).

- Stoll, Mark R., 2015, Inherit the Holy Mountain: Religion and the Rise of American Environmentalism, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, Bron, Editor-in-Chief, 2005, Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature, New York, NY: Continuum.

- Warren, William, and Barry Browman, 2005, Spirit Abodes of Thailand, Singapore: Marshall Cavandish Editions.

- Worster, Donald L., 2008, A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sacred banyon tree and spirit house in Bangkok, Thailand.

Sacred Cave, Northern Thailand